The Golden Age of Comics (1930s to late 1940s) was beginning to shift even before the official start of the Silver Age (1950s to early 1970s.) Heroes similar to Superman and Captain America, who had kept mankind safe and battled monsters in the dreams of children during the ravages of WWII, were slowly but surely disappearing from the shelves.

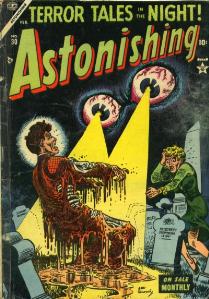

In their place were tales of terrifying creatures to shift dreams to nightmares, along with crime dramas that mirrored the love affair the public had with the 30s gangsters. In the classic battle of good versus evil, good was losing the money battle. Jingling pockets were quickly emptied as kids gushed over zombies and vampires, mob bosses and, on the opposite side, cartoon slapstick where characters were blown up and recovered instantly.

In 1954, Congress reacted to the ever-darkening tone of comics by forming the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. The hearings made claims that young minds were being warped. It echoed through the halls of Congress and several senators successfully tied juvenile delinquency to the images on comic pages. Fearing governmental regulation, the comic book industry decided self-regulation was preferable. They formed the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) and from that the Comics Code Authority (CCA) was born.

In 1954, Congress reacted to the ever-darkening tone of comics by forming the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. The hearings made claims that young minds were being warped. It echoed through the halls of Congress and several senators successfully tied juvenile delinquency to the images on comic pages. Fearing governmental regulation, the comic book industry decided self-regulation was preferable. They formed the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) and from that the Comics Code Authority (CCA) was born.

Based loosely on the Hollywood Production Code of the 1930s and the code of the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers of 1948, the terms of the CCA cut the heads off zombies and shot gangsters (and their molls) right in the heart. No longer would there be creatures of the night like vampires or shapeshifters. Crime couldn’t be glamorized and love depicted in drawn pictures would be pure as the driven snow (and sex would always be within the confines of marriage.) Some of the many original requirements of the CCA were:

- Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal.

- All lurid, unsavory, gruesome illustrations shall be eliminated.

- Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism and werewolfism are prohibited.

- Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used or shall be published only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue and in no case shall evil be presented alluringly, nor so as to injure the sensibilities of the reader.

- Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at nor portrayed.

- Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.

Technically speaking, no publisher was required to adhere to the CCA, but shop owners began to demand the CCA-approved seal on the cover or they wouldn’t sell it. Best-selling lines were scrapped overnight and artists and publishers alike desperately scrabbled to find footing among the guidelines.

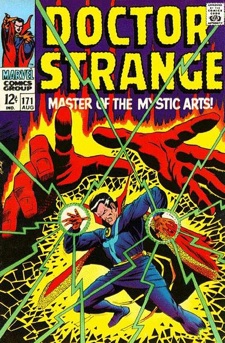

Magical and mutant powers and gods of old began to emerge as an alternative to vampires and zombies. A short lived character in the Golden Age, Doctor Fate, reemerged from DC and had his contemporary at Marvel with Doctor Druid (also known as Doctor Droom.) The Green Lantern, with his magic lantern ring, likewise was given new life. Fantastic Four and Thor were launched, as were Flash and Spider-Man. Some of the Golden Age style of heroes were reborn in those titles. But there had to be a way to satisfy the dark tastes of the audience who liked zombies and gangsters while staying within the CCA.

Magical and mutant powers and gods of old began to emerge as an alternative to vampires and zombies. A short lived character in the Golden Age, Doctor Fate, reemerged from DC and had his contemporary at Marvel with Doctor Druid (also known as Doctor Droom.) The Green Lantern, with his magic lantern ring, likewise was given new life. Fantastic Four and Thor were launched, as were Flash and Spider-Man. Some of the Golden Age style of heroes were reborn in those titles. But there had to be a way to satisfy the dark tastes of the audience who liked zombies and gangsters while staying within the CCA.

Enter the Silver Age concept of angst. It’s a mainstay of urban fantasy today, but the concept of a hero who was flawed was fairly new in the 1950s. Dr. Strange was a favorite of mine as a child, even though I discovered the older issues in stripped versions at small-town auctions. The Sorcerer Supreme was my introduction to the concept of urban fantasy before the genre had a name. He struggled with his powers right on the page, always fighting the battle—not against the villains, but against the magic inside him. Keeping the dark power in check and his mind always focused on doing good in order to stay sane, he fought against others of his kind. If he’d been introduced in the Golden Age, he might have been on the same side as the bad guys.

Enter the Silver Age concept of angst. It’s a mainstay of urban fantasy today, but the concept of a hero who was flawed was fairly new in the 1950s. Dr. Strange was a favorite of mine as a child, even though I discovered the older issues in stripped versions at small-town auctions. The Sorcerer Supreme was my introduction to the concept of urban fantasy before the genre had a name. He struggled with his powers right on the page, always fighting the battle—not against the villains, but against the magic inside him. Keeping the dark power in check and his mind always focused on doing good in order to stay sane, he fought against others of his kind. If he’d been introduced in the Golden Age, he might have been on the same side as the bad guys.

The Silver Age was an era of switching sides. Villains like Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, the children of Magneto in X-Men fame, flip-flopped between good and evil. In one issue you cheered as they joined the good guys and in the next, mourned when they fell off the wagon. They weighed the benefits of good and evil and couldn’t completely decide which was better. We watched the journey and decision-making process and felt for them. Our own childhood emotional turmoil was displaced by the angst on those richly colored pages. Comics were reality television before such a thing existed, the short version of the graphic novels on the shelves today.

The Bronze Age (1970s to the mid 1980s) only added to the conflict and darkness of soul. Marvel Comics, at the request of the government, did a three-part issue on drug abuse in 1971. The CCA rejected the topic. So the publisher did the only thing it could to satisfy both sides—they removed the approved seal from the covers of Amazing Spider-Man issues #96-98 and sent it out. The CCA revisited the topic of drugs and along with multiple changes in the early 1970s, began to allow more controversial topics and…more monsters. I remember the Spider-Man issues well and owned them for years. But the controversy surrounding the topic confused me. Seeing a hero deal with the very issues I was facing at school wowed me, along with many of my friends. It was, and is, still one of the best trilogies of the series in my mind.

Darker anti-heroes began to emerge, too. Ghost Rider, and his hellspawn fire, was introduced along with Son of Satan (also known as Hellstorm) as a semi-good guy who struggled against his father’s heritage.

Interestingly, Young Adult fantasy was launched during this time and I was always sorry one title didn’t do better on the shelves. Amethyst, Princess of Gemworld was actually a very strong concept—the bare beginnings of later book series like Harry Potter and House of Night. A normal thirteen year old girl discovers she was actually adopted by her human parents. She’s a princess in a magical realm, and when she’s in Gemworld, she’s in an adult body. Confronting the duties, politics, and yes…sexual awakening of an adult with a still-teen mind, Amy/Amethyst has to grow up in a hurry. It spoke to me, even though I wasn’t thirteen when it was introduced. It was urban fantasy at its heart.

Interestingly, Young Adult fantasy was launched during this time and I was always sorry one title didn’t do better on the shelves. Amethyst, Princess of Gemworld was actually a very strong concept—the bare beginnings of later book series like Harry Potter and House of Night. A normal thirteen year old girl discovers she was actually adopted by her human parents. She’s a princess in a magical realm, and when she’s in Gemworld, she’s in an adult body. Confronting the duties, politics, and yes…sexual awakening of an adult with a still-teen mind, Amy/Amethyst has to grow up in a hurry. It spoke to me, even though I wasn’t thirteen when it was introduced. It was urban fantasy at its heart.

Many claim the Bronze Age never ended, that the Modern Age doesn’t actually exist and all that happened was that publishers no longer cared about having CCA approval on their books. Both DC and Marvel launched imprints to publish more adult comics in the 1980s—which were similar to the underground comic movement started in the Bronze Age. The themes of urban fantasy-style storylines and heroes filled with turmoil have continued and prospered ever since and a wealth of titles have transformed to become “graphic novels.”

As both a reader of comics and an author of dark fantasy books, I’m thrilled at the turn of events. While I still love “bland” humor titles that prospered under CCA like Archie, Richie Rich, Little Dot and Baby Huey, I also love Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Dresden Files and Twilight in comic form—which would have appealed equally to Silver Age readers. I’m curious how all of you view the topic. Has the Bronze Age ended? Was the CCA a horrible thing or did it force a creative leap that led to our current urban fantasy craze? What do you think?

Cathy Clamp is a life-long comic book geek who later became a best selling author of urban fantasy and paranormal romance. Along with C.T. Adams, (the pair now write as Cat Adams) they author the Tales of the Sazi shapeshifter series and The Thrall vampire series for Tor Books on the paranormal romance shelves.

Their new Blood Singer series is their first on the SF/F shelves. The first book, Blood Song, released in June to exceptional reviews, and she finds it both fascinating and amusing that none of her books would ever have made it past the CCA censors. You can find Cathy on-line at their website, on Twitter or on the Witchy Chicks blog.